Demand for charter schools in Hawaiʻi continues to rise, yet the lack of adequate facilities hampers their expansion. Over the past three years, a group of educators proposed the establishment of the first charter school in the state focused on artificial intelligence and data science. With the approval of the state charter school commission, they aimed to operate from a modest campus in Kalihi. Despite the initial skepticism from the Department of Education (DOE), which raised concerns about low student enrollment in nearby schools, Kūlia Academy opened in the fall of 2023 and has since developed a lengthy waitlist. This innovative school appeals to families due to its unique curriculum and central location, according to director Andy Gokce.

While the overall public school enrollment in Hawaiʻi is declining, charter schools have witnessed nearly a 10% increase in enrollment since 2020, making them the only sector in Hawaiʻi’s education landscape to report growth during the pandemic. As the state considers closing smaller public schools, charter schools are actively establishing campuses across the islands, from urban Honolulu to the north shore of Kauaʻi. Since the inception of the charter school movement three decades ago, 40 schools have been launched statewide.

Collaboration between charter schools and the DOE remains limited, leading to competition for students and resources. Some charter school advocates argue that now is the time for both systems to work together. Public schools are grappling with increasing uncertainty around their resources as federal education policy evolves, and the shrinking student population in Hawaiʻi translates to reduced funding. Charter schools, which often lack guaranteed facilities, face challenges in finding affordable spaces that can accommodate their growing numbers.

Most charter schools operate on tight budgets, dedicating approximately 15% to 30% of their funding to facility expenses. These costs can escalate quickly, as evidenced by the closure of Hālau Lokahi in 2015 after spending around $33,000 monthly on facilities. The DOE received over $320 million for maintenance and construction this year, but charter schools largely depend on their annual budgets for facility costs, which also cover teacher salaries and educational resources.

Educational advocates believe that sharing campus space with underutilized DOE schools could benefit both systems. They argue that such collaboration could offer families more educational options while maximizing the use of state facilities. Despite directives from lawmakers to explore campus-sharing agreements, progress has been slow. In some instances, the DOE has suggested converting open campus space into state offices or leasing it for profit instead.

Concerns about enrollment should not hinder the growth of charter schools, especially in areas where demand exists, according to David Sun-Miyashiro, executive director of HawaiʻiKidsCAN. He emphasizes that charter schools attract diverse families from across the island, and their unique programs complement local education offerings.

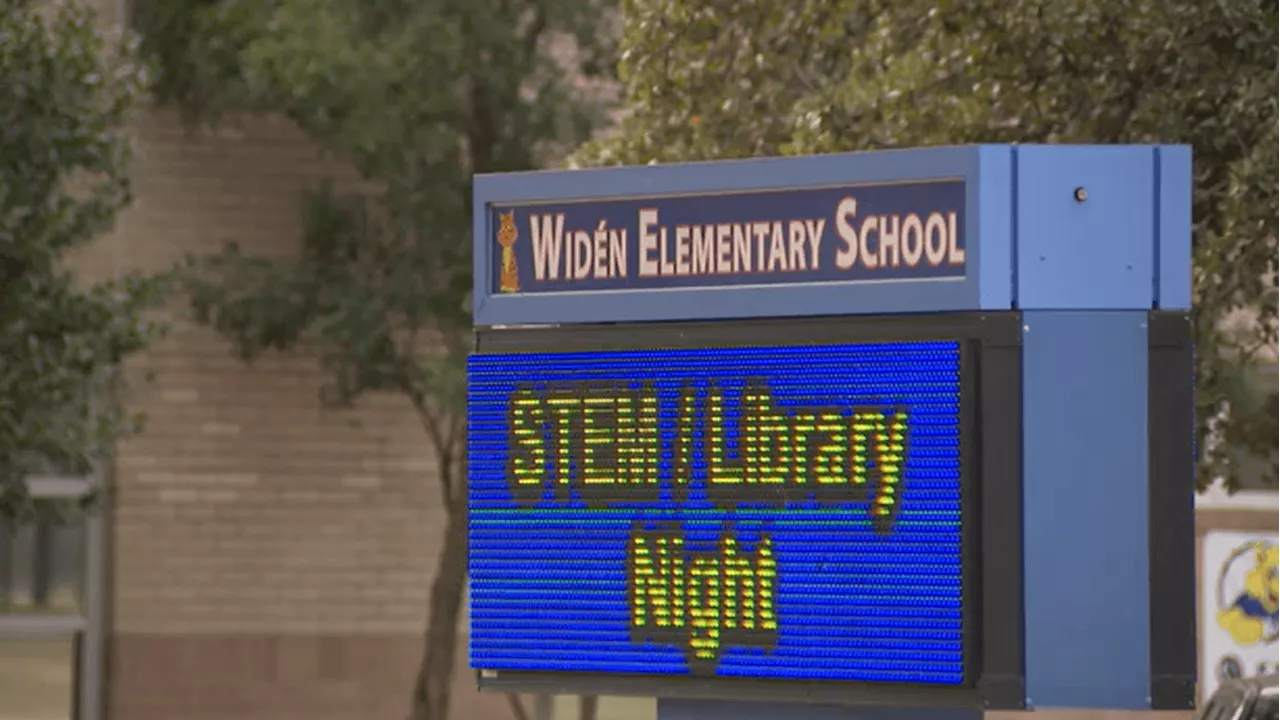

At Hawaiʻi Technology Academy’s Kauaʻi campus, students navigate between businesses in a strip mall environment, illustrating the challenges faced by charter schools in securing appropriate facilities. The unconventional setting has allowed the school to grow incrementally as office space becomes available, yet it poses limitations for student activities.

Previous attempts to build partnerships between charter schools and the DOE have met with hurdles. For example, in 2017, a facility-sharing agreement between the School for Examining Essential Questions of Sustainability (SEEQS) and Kaimukī High School was developed to utilize unused classrooms. However, changes in leadership led to SEEQS being required to vacate the premises in 2021, despite the high school continuing to experience declining enrollment.

Currently, no charter schools have formal campus-sharing agreements with the DOE, except for conversion schools that began as DOE institutions. In 2024, lawmakers introduced a resolution aimed at identifying unused DOE facilities and proposing policies to facilitate charter school access to these spaces. The proposal received strong support from charter school advocates but did not advance in the Senate.

Advocates for shared facilities argue that this model serves the interests of both charter and DOE schools. Todd Ziebarth, senior vice president at the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, notes that keeping schools open in shrinking neighborhoods can prevent difficult decisions that could be unpopular among communities.

Despite legislative efforts, the practical implementation of facility-sharing remains limited. The DOE has not closed a school since 2011 and has expressed interest in maximizing its campuses for revenue generation rather than collaborating with charter schools. Recent discussions revealed that DOE officials are open to partnerships but require detailed agreements on shared responsibilities.

As Hawaiʻi grapples with declining student numbers, some lawmakers suggest that creating new charter schools may not be the answer. Instead, they advocate for existing charter schools to share space with DOE campuses or for the conversion of traditional public schools into charter institutions. Such measures could address the challenges of limited resources while ensuring that educational needs are met in communities experiencing population shifts.

The evolving landscape of education in Hawaiʻi presents both challenges and opportunities for charter schools and the DOE. With innovative solutions and collaborative efforts, there remains potential to enhance educational offerings for families across the islands.