Nearly two millennia after the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius, researchers have employed advanced digital archaeology techniques to unveil the “lost Pompeii.” The eruption in AD 79 buried the thriving Roman city under thick layers of ash and debris, preserving its remains in a haunting snapshot of history. While many structures and artifacts have been uncovered since excavations began in 1748, significant gaps in understanding daily life and architectural styles remain.

Now, a team led by Dr. Susanne Muth from Humboldt University is using a combination of remote sensing technology, close-range photography, and traditional archaeological methods to reveal insights that were previously obscured. Their work is particularly focused on the Casa del Tiaso, a lavish residence in Pompeii that may have belonged to an influential family.

Reconstructing Lost Architecture

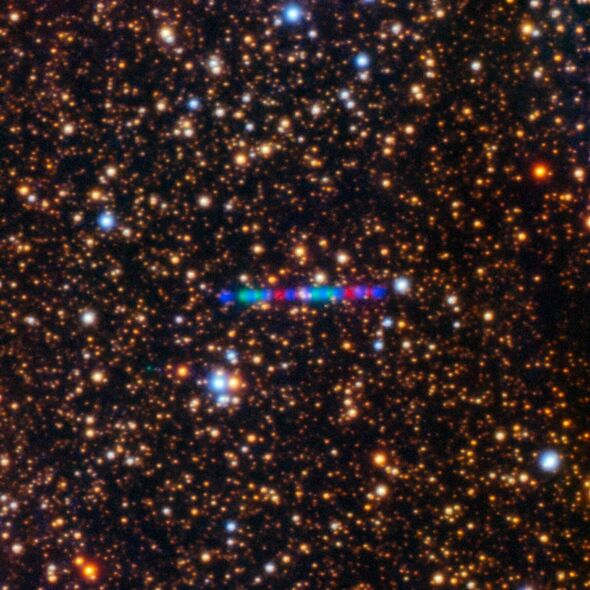

The Pompeii Reset project, which includes collaboration with the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, has produced new findings that could reshape perceptions of the ancient skyline. The project employs techniques such as LiDAR (light detection and ranging) and photogrammetry to document existing structures and create three-dimensional models. Such technology has allowed researchers to identify features that hint at previously unrecognized architectural elements, including the potential existence of towers within urban spaces.

“By reconstructing the lost architecture, we gain a more nuanced and historically accurate understanding of the ancient city and life within it,” Muth stated. The evidence gathered suggests that wealthy residents may have constructed towers to demonstrate social status, much like the villas outside the city walls described in ancient texts.

During a visit to Pompeii in 2022, Muth conceived the idea of digitally preserving the city’s cultural heritage. She recognized the challenges posed by climate change and the fragility of existing ruins, prompting the need for noninvasive reconstruction techniques.

Daily Life and Architectural Innovations

The archaeological park’s director, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, noted that the volcanic debris from the AD 79 eruption created a five-meter (approximately 16 feet) layer of ash, partially preserving upper floors. Evidence indicates that some inhabitants returned to the ruins decades later, adapting to the new environment by creating cellars with ovens and mills.

“Excavations initially focused on uncovering statues and wall paintings, sidelining the upper floors where ordinary citizens lived,” Muth explained. Recent findings have shifted this approach. “We discovered that the wealthier citizens also utilized these spaces, revealing more about their everyday lives.”

In the Casa del Tiaso, a monumental stone staircase leading to a second floor has piqued the researchers’ interest. Indications of an additional wooden staircase suggest that the upper levels may have served significant purposes, potentially including social gatherings and panoramic views of the city.

Archaeologists have historically overlooked the presence of towers within Pompeii due to the sprawling nature of Roman urban architecture. However, the findings in the Casa del Tiaso challenge previous assumptions. “These structures may have been a hallmark of wealth and prestige, similar to the country villas described by Roman writers like Pliny the Younger,” Muth noted.

The implications of this research extend beyond architectural curiosity. The discovery of potential towers provides a new lens through which to understand how social status was communicated in ancient Rome.

As the digital reconstruction of the Casa del Tiaso continues, the team aims to include every room and feature, while also monitoring the preservation state of Pompeii. Digital tools serve not only to visualize lost architecture but also to inform conservation efforts.

“Digital archaeology is much more than creating fanciful reconstructions,” Zuchtriegel emphasized. “It’s about understanding how these structures functioned and how they shaped the lives of their inhabitants.”

As the project advances, questions remain about the extent of tower-like structures in Pompeii and other urban centers. Ongoing research will explore how prevalent these features were among the elite of ancient Rome.

The work being done at Pompeii highlights the potential for digital technology to transform our understanding of historical sites. With more than 13,000 rooms excavated, and a significant portion of ancient Pompeii still buried, the findings from the Pompeii Reset project could provide crucial insights into the city’s architectural and social landscape for generations to come.