A team of international researchers has documented the first fossilized footprints of prehistoric elephants in the coastal dune deposits of Murcia, Spain. This significant discovery, attributed to the Palaeoloxodon antiquus, commonly known as the straight-tusked elephant, offers new insights into the movement of megafauna during the Quaternary period, particularly the Last Interglacial, approximately 125,000 years ago.

The findings are detailed in the study titled “New vertebrate footprint sites in the latest interglacial dune deposits on the coast of Murcia (southeast Spain). Ecological corridors for elephants in Iberia?” published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews. The research was spearheaded by a collaboration involving the University of Seville, the Andalusian Institute of Earth Sciences in Granada, and the University of Huelva.

Significant Discoveries Along the Coast

The research team conducted extensive prospecting campaigns along the Murcian coast, particularly in the areas of Calblanque and Torre de Cope. These efforts were coordinated by Carlos Neto de Carvalho from the Geology Office of the Municipality of Idanha-a-Nova and the University of Lisbon. Key contributors included researchers from the University of Seville, such as Fernando Muñiz Guinea and Miguel Cortés-Sánchez, along with experts from IACT-CSIC and universities in Portugal.

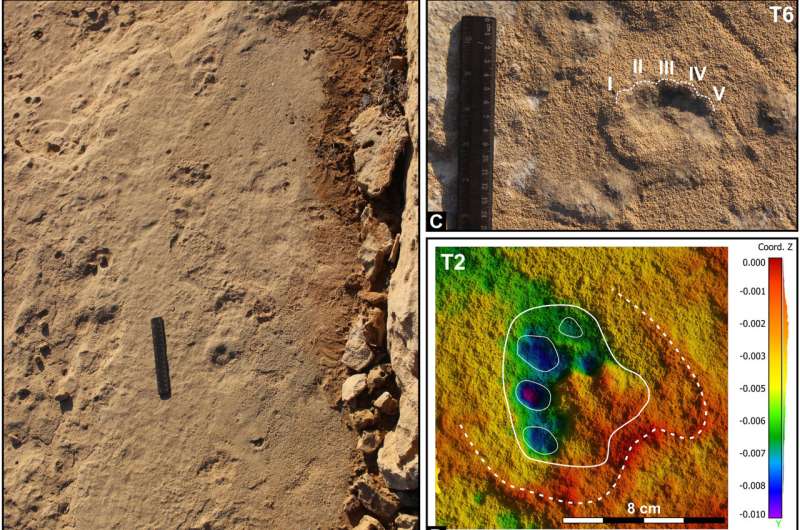

The most notable finding emerged from the Torre de Cope site, where a preserved trackway measuring 2.75 meters long was identified. This trackway, comprising four rounded footprints each 40–50 cm in diameter, reflects the characteristic quadrupedal gait of elephants. Analysis suggests that these tracks were made by an adult Palaeoloxodon antiquus, approximately 2.3 meters tall at the hip, weighing around 2.6 tonnes, and estimated to be over 30 years old.

In addition to elephant tracks, the research uncovered evidence of other mammals inhabiting this coastal ecosystem. Tracks of a medium-sized mustelid were found in Calblanque, characterized by a one-and-a-half-meter trail of ten nearly circular footprints, indicating slow movements near water sources. A solitary canid footprint measuring 10 × 8 cm, with claw marks, suggests the presence of wolves (Canis lupus) in this woodland habitat. Furthermore, bifid footprints compatible with red deer (Cervus elaphus) were identified, reflecting their movement through the dunes and scrubland.

Insights into Pleistocene Ecology

The findings support the hypothesis of coastal ecological corridors, facilitating seasonal migrations between Mediterranean forests and beaches during a more humid climate. This research not only enhances our understanding of prehistoric ecosystems but also suggests that these corridors may have been crucial for large mammals, including elephants, as they navigated the landscape.

The implications of this study extend to the historical context of the Iberian Peninsula during the Pleistocene. The coastal areas of Murcia likely served as climate refuges for various flora and fauna, providing vital routes for megafauna. The authors of the study establish a connection between these ecological corridors and paleoanthropological evidence, indicating a geographical overlap between the migration paths of elephants and Neanderthal habitation sites.

As a result, these coastal areas may have been resource-rich environments essential for both large mammals and Neanderthal populations, contributing to their survival and subsistence strategies. The research offers a comprehensive perspective on the interplay between ancient ecosystems and human activity, underscoring the significance of the findings in understanding our planet’s ecological history.

For further details, refer to the study by Carlos Neto de Carvalho et al in Quaternary Science Reviews, DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2025.109631.