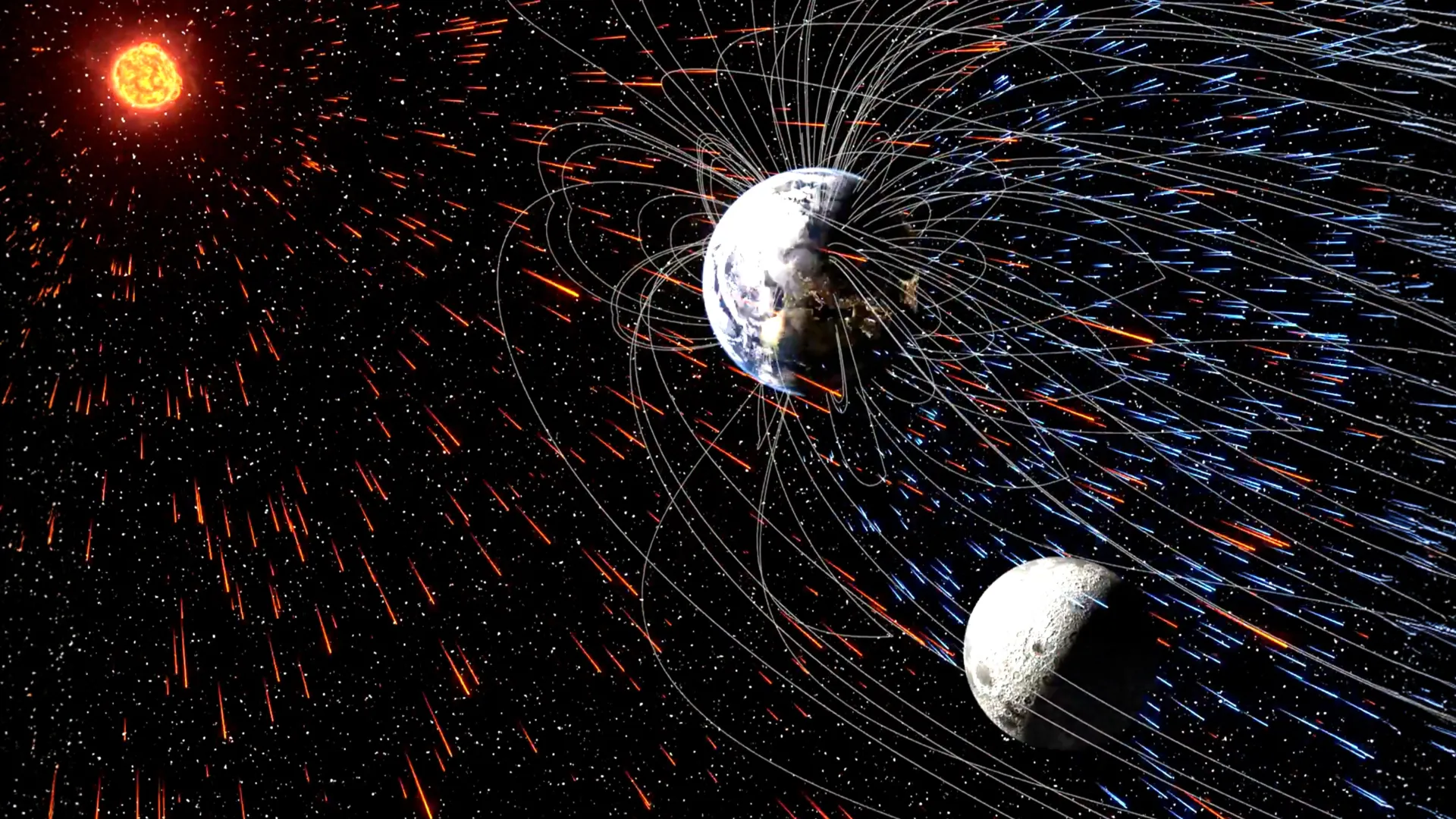

Earth has been delivering tiny fragments of its atmosphere to the moon for billions of years, according to new research from the University of Rochester. This transfer is facilitated by Earth’s magnetic field, which channels atmospheric particles into space rather than blocking them. The findings, published in Nature Communications Earth and Environment, shed light on the potential for lunar soil to serve as a historical archive of Earth’s atmospheric evolution, as well as a resource for future lunar missions.

While the moon may seem barren at first glance, it has been subtly accumulating materials from Earth over eons. Researchers have long wondered how these particles could travel the vast distance to the moon. The team at the University of Rochester, led by Eric Blackman, has concluded that Earth’s magnetic field plays a pivotal role in this process.

By analyzing lunar soil samples collected during the Apollo missions, scientists discovered that the moon’s regolith contains various gases, including water, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen. Some of these volatiles are known to originate from the solar wind, a constant stream of charged particles emitted by the sun. However, the quantities present, particularly nitrogen, exceed what solar wind alone could account for.

In 2005, researchers from the University of Tokyo proposed that these gases might have come from Earth’s atmosphere early in the planet’s history, before a magnetic field developed. Their assertion suggested that once the magnetic field formed, it would prevent atmospheric particles from escaping into space. The findings from the Rochester team challenge this notion, indicating that the magnetic field actually aids in the transfer of particles to the moon.

Simulation of Atmospheric Transfer

To explore how atmospheric particles reach the moon, the research team employed advanced computer simulations. The group included Shubhonkar Paramanick, a graduate student, John Tarduno, a professor in Earth and Environmental Sciences, and computational scientist Jonathan Carroll-Nellenback. Their simulations tested two scenarios: one without a magnetic field and another that reflects present-day conditions with a robust magnetic shield.

The results revealed that particle transfer to the moon is significantly more effective under modern conditions. Charged particles from Earth’s upper atmosphere can be dislodged by the solar wind and subsequently follow the magnetic field lines, some of which extend far enough into space to intersect the moon’s orbit. Over billions of years, this mechanism acts as a slow funnel, allowing small amounts of Earth’s atmosphere to accumulate on the lunar surface.

Implications for Science and Future Exploration

The implications of this research are profound. The moon may hold a chemical record of Earth’s atmospheric history, providing insights into the evolution of Earth’s climate and life over billions of years. Additionally, the steady influx of atmospheric particles suggests that lunar soil may contain valuable materials, such as water and nitrogen, which could support long-term human activities on the moon. This would lessen the reliance on resupplying from Earth, facilitating more sustainable exploration.

Parmanick highlighted that the study’s findings could extend beyond Earth’s moon. “Our research may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars, which lacks a global magnetic field today but had one similar to Earth in the past,” he noted. This perspective could help scientists understand how planetary environments evolve and affect habitability.

The research received support from NASA and the National Science Foundation, underscoring its significance in the broader context of space exploration and planetary science. As scientists continue to study lunar soil and its history, they may uncover even more about the connections between Earth and its celestial neighbor.