In the rapidly evolving landscape of manufacturing automation, the importance of tool geometry remains a vital aspect of process efficiency. Even as advanced technologies like CNC controls and industrial robots become more prevalent, the fundamental physics of cutting still hinge on the precise geometry of the tools used. This reality underscores the need for manufacturers to prioritize tool selection alongside their investments in smart machinery.

The Irreplaceable Role of Tool Geometry

Despite the sophistication of modern manufacturing systems, including smart CNC machines that adjust feeds and speeds in real-time, the cutting action ultimately occurs at the intersection of a small piece of carbide and the workpiece material. Factors such as helix angles, rake angles, flute counts, and edge preparation dictate crucial aspects like cutting forces, heat generation, and chip flow. If these parameters are not optimized, even the most advanced monitoring systems will struggle to maintain stable and productive operations.

Research conducted by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) highlights the significance of this relationship. In various experiments, the integration of AI and sensor technology into machining environments assumes that the underlying cutting tools are appropriate for their tasks. This connection illustrates that while AI can enhance production processes, it cannot compensate for poor geometry choices.

Understanding the Impact of Geometry on Production

Consider a typical high-mix job shop where a single CNC cell may switch between machining stainless steel brackets and aluminum housings throughout the day. On the surface, it may seem that CNC parameters can be adjusted easily through programming, and the robotic systems will handle the transition without issue. However, the selection of tool geometry plays a critical role in determining how effectively these operations can be executed.

Recent studies indicate that even minor adjustments in tool geometry can lead to significant changes in both cutting forces and surface quality, affecting the overall manufacturing consistency and tool longevity. For instance, optimizing micro-geometries has demonstrated reductions in cutting forces and improved surface roughness, yielding substantial benefits across various parts and processes.

This sensitivity highlights the necessity for manufacturers to carefully categorize tools in their databases, as tools with the same nominal size can behave quite differently based on their specific geometrical attributes. The choice between a high-helix, polished three-flute end mill versus a four-flute general-purpose design can greatly influence performance, particularly in demanding applications.

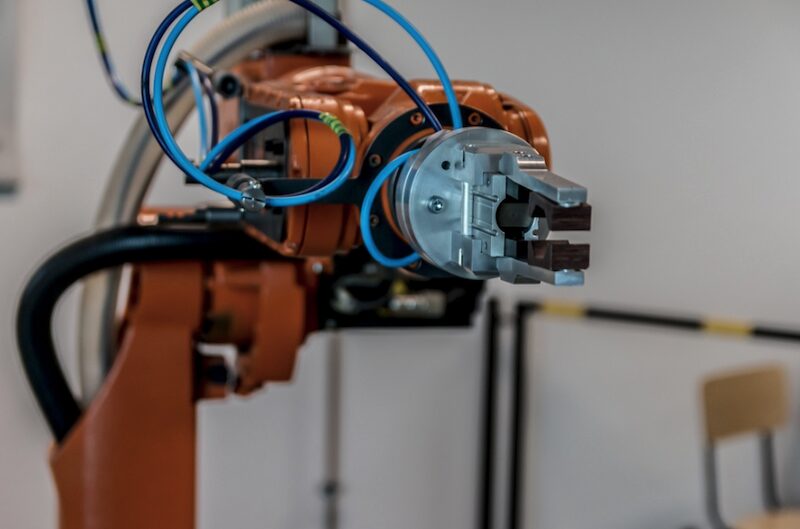

When robots are introduced into the workflow, ensuring process robustness becomes even more critical. Unlike a human operator who can adjust settings upon detecting unusual sounds, robots will continue to operate under potentially unfavorable conditions. Therefore, the geometry of the cutting tools becomes a frontline defense against unnoticed issues that could compromise production quality.

For example, utilizing a tool with a small corner radius can help manage stress and reduce chipping when machining hard stainless steel, extending tool life and maintaining dimensional accuracy. In automated settings, this attention to geometry can mean the difference between successful production runs and extensive rework.

Best Practices for Tool Geometry Management

To maximize the benefits of advanced CNC and robotic technologies, manufacturers should formalize their tool geometry decision-making processes. Standardizing “tool families” by material type and intended operation, rather than merely by diameter, is a practical approach. For instance, specifying high-helix, polished three-flute tools for aluminum applications can enhance performance and efficiency.

Additionally, when introducing new parts into a robotic cell, it is essential to evaluate not just the cutting speeds and feeds but also the specific geometrical characteristics of the tools being used. Questions such as whether the flute configuration will effectively clear chips from the workpiece, and if the corner design is robust enough for the expected engagement, should guide tool selection.

Finally, feedback from production experiences should be integrated into the company’s standards. When specific geometries consistently yield better outcomes—such as improved surface finishes or fewer instances of overload—these should be documented as best practices for future projects. Over time, this approach will create a comprehensive library of geometries that naturally support the automated processes being developed.

The manufacturing landscape is undeniably shifting towards smarter systems, yet the foundational role of tool geometry cannot be overlooked. By treating geometry as a primary consideration in manufacturing design, companies can unlock the full potential of their advanced technologies, ensuring that every tool, sensor, and robot works in harmony to deliver optimal results.